But not all elementary schools have that same wonderful environment. Our experience at Alice M. Curtis, for example, was not the same as our time at Leigh.

Anyway, all this is to say, that Alexander had a conflict with a couple of the neighbour kids, who began quizzing him on math facts. Now, Alexander is honestly doing very well with math. He's only in kindergarten, but is working his way through Beast Academy level 1. There's been no formal mention of multiplication in his book, though he is working on grouping numbers (which is foundational to multiplication), and knows about multiplication from his older siblings talking about it.

"It's like double addition," he explained to me, which I wouldn't say is a correct answer, but which shows that he's at least thinking about things.

So these neighbours—who are in grades 1 and 2—began quizzing him—the lowly homeschooled kindergartener—on math problems. When he was able to answer all the addition and subtraction questions they could throw at him, they asked him what 300 × 0 was.

Zoë is in grade three and she has been learning multiplication this year. He spends quite a bit of time watching over her shoulder, and he knew that often when there is a 0 involved you just...can add the zero to the end. So 300 × 0 must be 3000!

That was the answer he gave.

The rule he was thinking of was what to do when multiplying a number by ten. There's a different rule when multiplying something by 0, but he didn't know that! Because he's in kindergarten.

These girls started teasing him so hard!

"The answer is 0! How could you not know that? Everybody knows that! I learned that in kindergarten! I can't believe you didn't learn that in kindergarten! Haha!"

He was distraught. I had him tell me what the girls had said (they're sweet girls but, oh boy, they do know how to gang up on a kid).

"They're lying to you," I said. "They did not learn that in kindergarten or, if they did, they learned it the same way cruel you learned it just now."

"That's true," Miriam pointed out. "You're in kindergarten...and now you know."

What wonderful socialization skills they pick up in school these days.

"I'll bet that some older kids pulled the same stunt on them when they were in kindergarten, made them feel really dumb for not knowing something they didn't even need to know yet. But, buddy, neither of those girls is learning multiplication at school. Multiplication isn't even mentioned in the Georgia State Standards until grade three* and Zoë didn't start learning multiplication in Beast Academy until this year and she's in...you guessed it...third grade. So you still have time to learn. Don't worry about what those girls say. You're right on track for where you need to be."

*Okay, so it actually does say that some skills learned in grade two are building the foundation for multiplication, so the word is found in the second grade standards, but that's the only mention. Multiplication instruction does not begin until grade three.

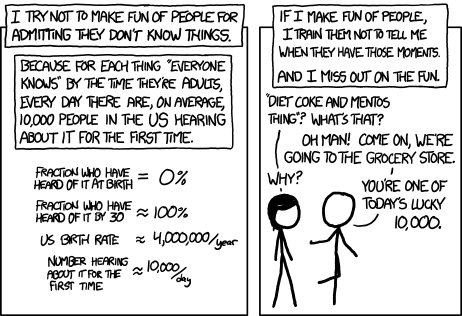

Anyway, our lesson was based on comic #1053 XKCD:

Benjamin shared how some homeschool boys laughed at him when he didn't know how to throw a football back to them (so you see...negative socialization doesn't only occur in a public school setting). Perhaps I should be a better homeschool teacher and make sure he knows how to throw a football. But Rachel shared that when we moved to Spanish Fork (as public schoolers), she didn't know how to throw a football correctly, so her friend Tayah said, "I can show you how to throw a football. Let's get together to work on it!" And Rachel learned how to throw a football.

We talked about how we could share the rule of [n × 0 = 0] with someone who didn't know it previously. It's a pretty cool trick, really! Many symbols in mathematics have many words to describe them. When you see + you can say "plus" or you can say "and," for example. When you see - you can say "subtract," "minus," or "take away." And when you see × you can say "times" or "multiplied by" or "groups of."

Let's think about it as "groups of."

How many do you have if you have 15 groups of...0?

0!

How many do you have if you have 5,682 groups of...0?

0!

If you have 23 friends and you give each of them...nothing...how many presents did you give away?

0!

If 10 pumpkin plants sprouted in your garden but none of them grew any pumpkins, how many pumpkins do you have?

0!

So that's pretty neat! Anything multiplied by 0 is 0.

The whole table was suddenly abuzz with the magic of multiplying by 0.

"You can even get really complicated, like...what is 4 × 6 × 1000 × 16 × 7.23408 × 0 × -34? Still 0!"

"It's the best when you see something times zero on a quiz or test! There's no hesitation—you know the answer is 0!"

Alexander was laughing now, so proud to understand, and be part of the crowd who can multiply by 0...in kindergarten!

We told the kids that that is how they want to approach every situation where they find someone who doesn't know something. Show the magic, share your passion, let it be positive. Don't shame them because not having been taught something, not having learned something, isn't a moral failure!

Though, to be fair we shouldn't shame others for those either, I suppose...I'm always sticking my foot in my mouth like that. For example, once Rachel was with me while I was supervising a number of rather rowdy primary boys (around the ages of 7–9) and two of them started punching each other (not in a fighting, full-of-anger way, but still enough that I needed to put a stop to their behaviour before things got out of hand), so I said, "Boys, simmer down. We don't punch our friends!"

"Mom!" Rachel said. "We don't punch anybody!"

"That's right," I said. "We don't punch anybody. There shall be no more punching today—friend or foe!"

Anyway, my point is that not knowing something is relatively neutral. There are so many things to learn about, so many things to do, that it's impossible to know everything. There are too many good books, good movies, good games, good food, good people, good places... We will never get to experience it all. Our job is simply to seek after good things, but there is no way for us to find or experience all good things; we must be content with some good things, or at least be content with the good that we've found (while also seeking more goodness...and sharing that goodness with others in an uplifting way).

This reminds me of my Uncle Bruce's recent post, chiefly: "...we are multi-dimensional beings. Scoring higher on one dimension means little when there are other dimensions where [we] score lower."

His post was about humility, and I think the method of approaching situations illustrated by the XKCD comic is precisely illustrative of that attribute. A prideful reaction is to point and laugh. A humble reaction is to—with gentleness and excitement—show and share.

We also talked about a scenario where I was asked by someone to explain my thesis research, so I told them that I was looking at religious portrayals in graphic novels.

"Ew. I hate graphic novels. Graphic novels are so dumb. They're impossible to read; they're not even real books," they said.

"Yeah," I agreed with them. "I haven't always been a fan of graphic novels either. I used to actively avoid them because—like you—I didn't think they qualified as literature, but after studying the form and learning how to read them—because it really does take a different set of skills than reading a text-only book—my perspective began to switch. For example, have you heard of Shannon Hale's..."

"I hate Shannon Hale. Her books are so dumb. Every plot is just a regurgitation of a fairy tale. She has no original content. She's such a boring author. I don't know how anyone could stand to read more than the first few pages of any of her books. She..."

"Well," I said. "She has a graphic novel trilogy about her experience in middle school and it was so interesting for me to read them because she doesn't shy away from showing her religious experience on the page and..."

You get the picture.

We talked about how deflating my conversation was. This person's comments just took the wind right out of my sails. And it was hard for me to continue talking about my research because...I felt so attacked.

(And Shannon Hale, if you're reading this, which you probably aren't, just know that I think your books are marvelous and I recommend you to everyone. I just gave a little neighbour girl (one of the girls who was teasing my son earlier, actually) copies of Princess in Black #1 and #2 to read while she's on a long car ride to her grandparents' house. She and her baby sister dressed up as The Princess in Black and Princess Sneezewort for Halloween and they were adorable together. I was so excited to see their costumes because I had recommended the series to her mom as a good "transitional" novel for her daughter to read and she just fell in love with the series. She's been checking them out at the library one by one, but I just picked up a bundle of books from a friend who was weeding her collection, and the bundle included these two books and I figured she'd like to have a couple copies of her very own (since we already have copies in our collection. Just wait until she finds out about Princess Academy and Goose Girl! There is so much joy and goodness awaiting her!)

So we role-played how person B could have responded differently to my explanation, while still maintaining their opinion (of not liking graphic novels).

For example, "Interesting. I've never really understood the pull of graphic novels. I've tried reading a few but I just didn't enjoy them. What merits do you see in the form compared to textual novels?"

Andrew was actually really good at coming up with curious questions to ask. He's more practiced at it than I am, probably because he's a professor. Part of his job is to be interested in research that's not his, to ask probing questions that help his students know how to dig in deeper, to be interested and curious about things, to build people up and support them in their pursuit of good things (knowledge and things like that). He has a pretty cool job.

I talked about how my own advisor admitted she's not a huge fan of graphic novels, but that she interested in why people are interested in them. She's not religious, but she's interested in why people are religious. She asked me many wonderful, curious questions about my research—research that wasn't precisely up her alley, so to speak, but research that enriched her life, nonetheless, because she was curious about it.

We talked with the kids about the importance of being curious, not judgmental (which is not a quote from Walt Whitman, as the character Ted Lasso says it is...it's just an anonymous quote that makes the rounds).

Somehow we memorized 18 passages this year. I honestly didn't think we would do it, but we did! Everybody but Phoebe can say them all. So we're just brushing up on those, taking turns choosing which ones to recite, and in December we'll start on Christmas scriptures.

No comments:

Post a Comment